It just dawned on me that I hadn’t made a blog post lately. I am sorry about that! Life sure has a funny way of getting in the way of my best made plans….a whole BUNCH of LIFE going down! *sigh*

Besides all that–My plants have been entertaining me regularly with unexpected blooms, offshoots/pups emerging & the odd stress-color change happening here and there. I had been taking pictures, all the while, with both my Nikon camera and my phone. Still, I didn’t think to transfer any onto my computer. Maybe because every time I sit down at my computer, I get stuck doing tedious revisions to work projects, answering lengthy e-mails to friends & family, or getting stuck on an always ill-timed Skype call. Modern life & Technology really ticks me off most days! Can you tell?

I do recall I promised to share more pics of my fave Bromeliad, Bromelia balansae, as it progressed through its blooming cycle. I am glad I took pics at the time, because TODAY, it is looking pretty damn sad. 😦 It is at the point where the flowers have all bloomed out, dried up and dropped off. All it’s scarlet color is gone and it is back to plain ol’ green, and the leaf tips are all drying up. Soon, the berries will form and color up to a golden-yellow (see Intro page of this blog to see a picture of the fruiting habit of B. balansae). Well, that is just how it goes. I’ve got plenty more in the backyard to replace it with, though I will probably just allow the pups to overtake the gradually dying mother plant (as it is a terminal blooming species).

I’ve still been having trouble finding local or online sources for other Bromelia species. When I contact by e-mail or call many nurseries, they think I am asking about BROMELIADS and are like, “Oh YES! We have many different Bromeliads.” I am glad at that point they can’t see me make my “Close my eyes, furrow my brow, lift my glasses up on my forehead & rub the bridge of my nose with my thumb and forefinger” gesture! Usually, this is when I hear the SAME QUESTION asked by over 30 different “Bromeliad Specialty” Nurseries: “Have you tried growing Androlepis, Dyckias, Deuterocohnias, Hechtias, or Puyas? They are usually much easier to find and MUCH easier to HANDLE—Bromelia species have VERY vicious barbs and because of this, aren’t found very often in cultivation!” Yeah, Got that—Don’t care. Please carry more Bromelia species before I go INSANE!! I MUST HAVE MOOOOOOOORE! Despite the difficulty in finding them, I was able to obtain a few more species. Bromelia flemingii (a VERY SMALL offset). B. macedoi (also on the small side) & B. sp. French Guiana Holst (large offset, but it suffered some shipping stress–I hope it snaps out of it!) These two last plants I was able to buy from Tropiflora Nursery in Sarasota, FL. I think I actually bought the last 2 offsets they had available. I’ll take more pix when they have had a chance to grow a bit and settle in.

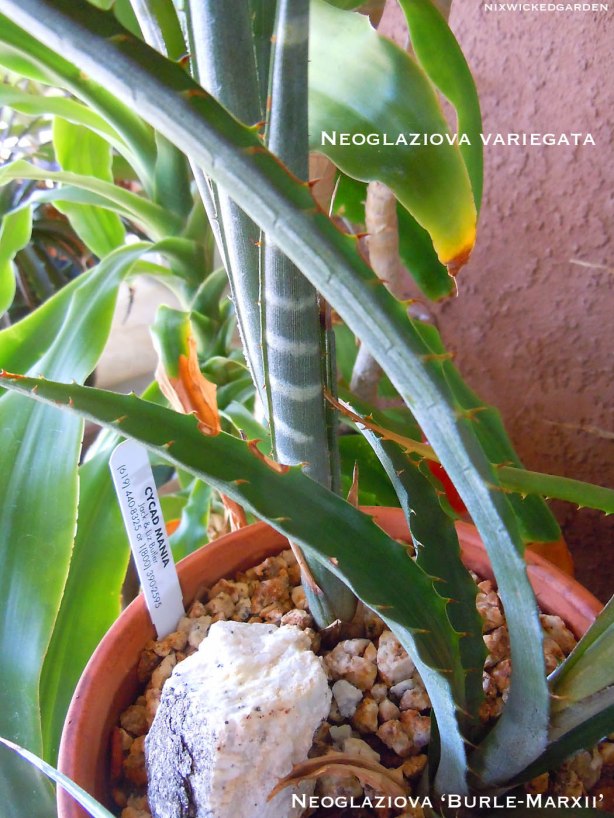

Clockwise from top to bottom (7 o’clock spot): Neoglaziova variegata & Neoglaziova burle-marxii (temporarily both in same pot) Bromelia sp. Fr. Guiana Holst, Agave bracteosa var. “Monterey Frost”, Bromelia flemingii pup, & xEnchotia “Ruby”

Detail of Neoglaziova variegata (white horizontal banding) & Neoglaziova burle-marxii. Purchased from Liz Butler.

Neoglaziova are an odd and small genus of Terrestrial Bromeliad. I believe there are only 3 identified species of Neoglaziova: N. variegata, N. concolor & N. burle-marxii. All have very attractive forms, but are armed with backward facing barbs to help protect them in their native habitat from being eaten by ravenous grazing animals. They are an important part of localized markets in South America where the plants tough leaf fibers are woven into fabrics, used to manufacture fishing nets and rope, as well as coarse woven goods. These species can be found in various arid regions in north-eastern Brazil. They form large clumps and at maturity, tall scarlet inflorescences with red petals rise from the center of the tall strap-like olive-drab leaves.

Acanthostachys is another small genus of Terrestrial Broms–Only 2 species! (Acanthostachys pitcairnioides & Acanthostachys stobilacea). See now. THESE are the types of plants I want to hear about! I bought a pup of each and before I knew it, BAM! I’ve got thriving colonies (or clumps) of the entire genera of Acanthostachys. 🙂 lol Most Bromeliad genera have HUNDREDS of different species, and a hundred more cultivars and hybrids. As an addicted collector, it becomes a very unrealistic goal to think I’ll ever have them all in my possession. Then again–if I win the lottery…. OK, Back to THESE plants: The leaves are slender & long, dull green to reddish-brown depending on light intensity and are whip-like in appearance, with serrated edges. These plants are very easy to handle and repot, as the serrated points don’t hurt–unless you slide your hand along its edge…So, don’t do that! An attractive long-lasting inflorescence develops at maturity (halfway up the leaf-stem in A. strobilacea. Between the leaf bases in A. pitcairnioides). These resemble tiny pineapples with orange-red bracts and yellow petals. The species are self-fertile and when ripe the berries that develop after blooming can be planted for propagation. Because of its form, Acanthostachys strobilacea is very attractive for hanging pot/basket culture, grown in bright, filtered light.

I am now realizing—if I try to write a paragraph or two for each plant I want to share in this post, I will be up till AT LEAST 3:30AM—it is now 10:30PM!!). I think what I will do is go ahead & post the photos with captions then add info on them later as I have more time. See what happens when I wait too long between posts? Shame on me!! (More info to come 😉 )

Tillandsias are really cool plants—what they don’t have in spines they make up for with their “scales” or trichomes. Some species are so jam-packed with these tiny scales that they appear to be coated with X-mas time “snow spray”. Many other bromeliads species have this visible scurf, as well. Whether growing on rocks, tree hosts, or in the soil, a large majority of bromeliad species live in habitats characterized by at least one, but more commonly by a combination of physical restraints—sunlight is frequently excessive, whereas water and nutrients are in short supply for at least part of the year. Trichomes are a characteristic universal to all bromeliads equipping them to deal effectively with one or more physical restraints. Many are just too small on some species to be viewed with the naked eye. These scales are epidermal appendages, usually hairlike in other plant families, common to many plants, but here on bromeliads are a modified, strange kind of shield-like trichome observed on all bromeliads that despite the differences found among various genera, they can be considered closely enough related to be placed into a single family.

The function of the trichome on the Tillandsias leaf shoots has become more modified as compared to more primitive members of the Bromeliad family with more specialized ones. In terrestrial bromeliads, water and nutrients are taken into the plants via their root system, so their trichome structures are simple and are mainly located on the underside of leaves around the leaf pores as a protective device against water loss. In bromelioids (or tank-type water catching tillandsioids) trichomes have become more complex in structural arrangement and they can now absorb water and nutrients. Atmospheric Tillandsias are even further advanced, or evolved, as to absorb water and nutrients from the air and water vapor such as fog, rainfall and dew.

My Tillandsia pruniosa bloomed for me and I was very excited to have the chance to snap some pics indoors (where he lives) and “posed” outside in a Queen Palm. T. pruniosa is an epiphyte that grows on trees at elevations from near sea-level to 1,200 meters in Florida, southern Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean islands & in South America from Ecuador into Brazil making it a VERY widely distributed species. It has come to be known as an “ant plant”, or pseudobulbous myrmecophyte. Its leaf-sheathes grow curved in such a way as to give the plant an outward appearance of a root-bulb, like a turnip. It isn’t solid or heavy—and its many-compartmented structure is very attractive to tiny ants as it gives them a ready-made shelter in which to move into! Ant Condos 😉

New Hechtia addition to my collection: Obtained from Andy Siekkinen, it is a “hybrid from the bees”–a botanical garden seedling labelled Hechtia “Q”

Lophophora williamsii (aka: Peyote), has been called The Divine Cactus, Tracks of the Little Deer and Medicine of God by indigenous peoples of the Americas (and called “Dry whiskey” & “Devil’s root” by angry religious leaders.) It is a small, spineless, dome-shaped cactus with clusters of soft wooly hair that has been used by tribes for thousands of years in curing wide varieties of ailments, as well as ceremoniously celebrated and revered as a sacred herb. Many have reported that using this cactus lets you hear colors and see sounds. For many Native Americans, it brings an ability to reach out of their physical lives , to communicate with the Spirits, and to “become complete”. Lophophora williamsii ssp williamsii is the most potent of all mescaline containing cacti, containing upwards of sixty different alkaloids. Largely because of its special ability to alter the human state of consciousness, its use was demonized by the Roman Catholic Church when the Inquisition was introduced into Mexico in 1571, and by 1620 it was officially declared that the use of Peyote was the work of the devil (The Spaniards perceived that miraculous powers and communication with God as coming only from the observance of the Mass and from the miracles performed by the saints). So it became a major goal of Spanish religious leaders to stamp out the use of this “satanic gift”.

Hmm…..its no wonder I believe in Creationism. It just makes makes more sense. I do believe in God—I just don’t think that He/She is as much of a buzz-kill as organized religion would have you believe…

Origin: From South Texas, USA to San Luis Potosi, Saltillo, Huizahe, Coahuila and Tamaulipas, MX.

L. williamsii has many variations in growth pattern and flower color, most likely due to the extreme range in altitude and is further divided typically into two different forms—northern and southern. The “Southern form” is found from Entronque – Huizache, MX, and L. williamsii “Northern type”, is centered around Saltillo, Coahuila, MX.

They are quite easy to keep growing healthy here in the Desert. I was advised by my LW source to place them where they will get direct AM sunlight for at least a few hours, then bright indirect light for the remainder of the day. I was also advised to keep them elevated well above the ground since garden slugs find Peyote irresistible—What is the telltale evidence that they have feasted on the “buttons”? Fat, passed out slugs on the ground, surrounding your plant!!! One issue that will kill these arid-loving cacti is overwatering. I only water them every 15 days. They MUST be protected from rainfall and sprinkler over-spray. When cooler temps arrive (November, here), Peyote will enter a semi-dormant state, so they need to be wintered indoors near a bright window or be outfitted with overhead florescent bulbs on a timer so they get 6 to 8 hours of light. By April (here in CA Desert) they can be moved back outside, where they will soon bloom again, announcing that they are “back amongst the living!!”.

I’ve grown quite fond of these curious little plants and because I found a fantastic honest & dependable source for them, I felt compelled to start a mini-collection. Due to the prohibitive cost of these cacti and legal issues surrounding these guys (which I don’t want to start ranting about!), I will most likely not be purchasing more–at least, not for awhile. I just wanted to share their images with other plant-loving individuals, so you may see how interesting, beautiful (and rare) they are.

In my last blog entry, I posted some pictures & a bit of writing on Cereus Peruvianus (an ornamental NON-mescaline containing night-blooming Cactus). The two plants pictured below are “The Real Thing”, so to speak. These are 2 of 3 different Trichocereus species that I am currently growing. Trichocereus pachanoi (San Pedro) is a very hardy species. It is grows to a height of 5m and will branch at the base froming a small tree, it has up to four small yellow to brown spines on each areole. Trichocereus peruvianus (Peruvian Torch) has a similar range and habitat to T. pachanoi, although it is also cultivated on the coast of Peru. Unlike T. pachanoi, it has massive vicious brown spines, up to 10cm in length.

San Pedro is commonly used as an ornamental cactus which is still widely available for landscaping from local nurseries, particularly in desert states. Known to the natives as the sacred Cactus of the four winds. This plant is native to the western slopes of the Andes of Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador were it can grow to over 5 meters. An extremely hardy cactus, it does well in colder climates as it grows in the wild at altitudes of up to 3000 meters. The alkaloids present, including the majority of mescaline, reside in the first 1 cm of skin. The green chlorophyl containing tissue under the skin appears to be where the majority of the alkaloids accumulate. Old specimens can have beautiful night-blooming flowers to 22 cm across that have a lovely smell, said to smell of ” beach-nut gum “. This Cactus grows best in mineral rich, well-drained soil containing some organic matter. Enjoys bright, but not full Sun and can tolerate abundant watering, does well indoors in pots. Natural habitat is in soil rich in humus and minerals, adequate rainfall, and maximal exposure to sun and wind. This species is also popular as grafting stock for smaller, slower growing cacti, such as Lophophora williamsii. I will have to give this a try down the road!

Used traditionally in divination, diagnosis of disease, finding lost or stolen property, and to possess another persons soul. A form of the original San Pedro religion still survives to this day, around Huacananda, Peru.

Trichocerei are not illegal to grow for horticultral purposes in any state in the US. However, laws regarding Peyote cactus are VERY confusing and I’ve already stated I’m not going to “go there” in this posting!! I am growing mine strictly for horticultural purposes, though I am a member of the NAC and am a card-carrying local tribal member—-Just Sayin’…

Note: THESE plants I DO NOT have growing by the street where Stoners might easily steal them….

i will to by that bromeliad

Thanks for the post, it helped me identify a huge colony of bromelia balansae living in the yard. We’ve tried to “tame” them with no luck, as soon as one is uprooted, another shoots up somewhere else. It seems all the roots of each individual plant are connected to each other. They’ve gotten so out of control and taken over, is there any way to kill them (without putting harsh chemicals on the lawn)? Any advice would be appreciated!

Hi Chelsea,

Funny–I’ve never been asked how to kill a Bromeliad before! My Partner, I’m afraid, feels as you do about this particular species. He would like me to take them all out and plant flowering groundcover….Um, no thanks.

They are quite hardy and can even creep through fences and over stone block stacks. The only way to kill them without harsh chemicals is to till over them all with a heavy duty motor-tiller and chop them all to bits. You may want to rake out all the pieces and throw them away. They aren’t like yucca—they won’t grow new plants from portions of branch remaining. But if you happen to miss any hearts of the plants…they could still send out new “runners” or suckers—just like the common Ananas (Pineapple plants). The difference being, of course, that the Bromelia is truly wicked and can chew up your limbs like a shark.

I just love them to death–but, I do hope you will be able to get rid of your unwanted brood!

Thank you for the advice.

I realized the irony of my request for methods of killing your beloved plant on a bromeliad-lovers site, but figured I had nothing to lose! I can’t believe what a serious undertaking it will be. How deep do their roots typically grow? I want to make sure I go deep enough to get all the “hearts”. I’ve read that hydrogen peroxide 10% sprayed over the ground they cover will kill them, but in the center of the 10′ circle patch of them is also a beautiful oak tree I want unharmed.

Looks like old fashioned hard work is the way way to go… Thanks again for the help!

Hi again, Chelsea! You are lucky in that Bromelia seldomly have deep down reaching runners. They typically have shallow roots and runners not exceding 8-10″ deep. I have these crazy leather gloves that reach almost to my shoulders (I was given these by a Bromeliad collector in Los Angeles–now deceased. I think they are for handling hawks, eagles or something!) I am able to thin down my Bromelia thickets by grabbing the newest, smallest clones from the edges of the bunch, working my way to plants further in. If you grab them from the base, near the soil and pull them toward you, they pull up quite easily—provided the soil is well saturated! Also assuming you have industrial, “battle-ready” hand & limb protection. Best of luck to you 😉

I love this blog! Regarding the bromeliad killing question…why don’t you post an ad on Craigslist for free bromeliads, come dig them up? If I lived close to you, I’d surely come. Also, aren’t copper based fungicides toxic to bromeliads? I would be careful with this, I don’t know how toxic they are to the environment.

Nothing since 2013. Does this mean this blog is no longer active? Such a shame as I just found it. Really great content on terrestrial broms! Glad it’s been kept live, if not active, at least for reference. I’d love to find out some sources of plants from the author and get your thoughts on a number of species as we expand our collection in this group. My e-mail has been included in the submission of this comment. If the author (sorry I don’t know your name, but I can’t find an “about me” page or contact information) could please contact me, if you check this again. Really nice stuff here!